Reading Saiken

One of the richest sources of information on the pleasure quarters is the saiken (細見), the semi-official guides printed one to three times a year. Their primary purpose was to give a complete catalogue of all the ageya, teahouses, and brothels in the quarter, with exquisitely ranked lists of the women at each "house," quarter-wide price lists, and lists of all the entertainers available for hire. Most of the information is given in tables and contains only short segments of text, making it accessible to researchers with a limited command of Japanese. All you have to do is be able to interpret it.

This page is as much notes to myself as final product, so take the information with a grain of salt. If you have any corrections, email them to me and I'll update the page.

Early vs. Late Saiken

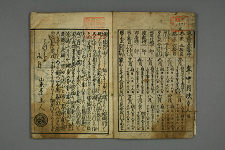

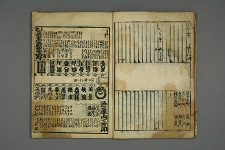

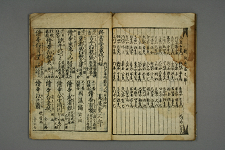

A page from Dyed by Human Ties, a 1713 Yoshiwara saiken. Under the crest to the right is the symbol for "supreme very best" and the name of the courtesan, who was almost certainly a tayû. Below her name is the kanji for "kamuro" (禿) and her kamuro's name. The following lines, headed by a black triangle, are a description of her personality and specialties. The layout of the listing under the second crest is similar, but the kanji for "supreme" are white, indicating that this courtesan is lower-ranking than the first courtesan. At the far left is a listing for a courtesan who merits only a "very best," but she is still high-ranking enough to have a kamuro.

© 2011 National Diet Library

The earliest saiken were chatty, descriptive books whose format owed a lot to the yûjo hyôbanki, the courtesan evaluations they descended from. The content was arranged in paragraphs, with headers and descriptive notes breaking up the flow of text--far more informative about individual women, but impossible to use unless you're fluent in 17th-century Japanese.

It's also an inefficient use of space. When the shortest description of a woman takes up one whole line, the saiken can become alarmingly long. The 1713 Yoshiwara saiken Dyed by Human Ties was printed in five volumes of about 60 pages apiece; the 1720 Yoshiwara saiken was printed in three volumes of about 100 pages apiece. There's no way to carry that stack of books around unobtrusively.

Some time before 1660, some genius hit on the idea of drawing the saiken as a map. The streets ran horizontally across the center of the page, with business listings arranged in cells to the left and right of the street. Within the brothels, women were labeled with a rank symbol (aijirushi) and listedin order within the ranks, with no other descriptive text; if there was any description of women, it moved to the introduction or to essays located elsewhere in the book. This method produced much shorter saiken: The 1738 Yoshiwara saiken, a pocket-sized version with only one side of the road printed on each page, is a single volume only 64 pages long. Although elements of this layout were used for portions of the 1660 and 1665 saiken, the full layout didn't become the standard until between 1720 and 1738 (the two saiken of that era that are available to me).

This new layout was such a success that it became the standard for all saiken, and was used with only minor variations until the end of the 19th century. It also became the standard for actors' saiken.

The new layout produced a saiken that's much easier for modern non-scholars to interpret. Information about each woman is communicated through symbols and positioning, so even someone who can't read the women's names can get an accurate head count and do demographic research. Being able to recognize (not read) names allows the researcher to track a woman's career within each house. House crests allow the researcher to follow each brothel's fortunes. Because this saiken format is the only one accessible to non-scholars, this page focuses solely on this format.

What You Need to Know

The first thing you need to know is how to read the handwriting of the era, which was... elegant. Let's call it elegant. The characters, called hentaigana (変体仮名) or "variant kana," were written in a cursive style called kuzushiji (崩し字). This is a good explanation of both, with a printable sheet of hiragana and their kuzushikana forms.

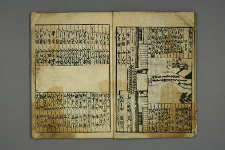

The second thing you need to know is the layout of the pleasure quarter. From about the mid-18th century, saiken are laid out as maps of the quarter, with the street running horizontally across the page and business listings arranged in cells to the left and right of the street. (Flip the saiken upside-down to read the names on the other side of the road.) Later saiken contain a smaller map of the quarter to orient the reader, but the example I chose for this page, the 1792 Yoshiwara Saiken hosted at Waseda University, skips an overall map in favor of jumping right to the main gate.

The third thing is how to navigate a saiken. This is a sample of section order and layout from 1792.

|

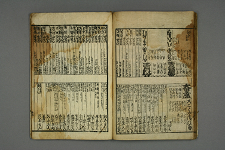

Page 1, on the right: The ranking and prices of the women of the quarter, with aijirushi, symbols denoting their rank. The ranks and aijirushi change over time, becoming more complex as the Yoshiwara grows; this is a comparatively simple example. Page 2, on the left: The foreword. |

|

Pages 3-4: The beginning of the street-by-street catalogue, starting at the entrance to the Yoshiwara. Before the main gate is the causeway to the Yoshiwara, with the names of the teahouses along the causeway written to the left and right of the road. Then comes the main gate, and the names of the teahouses and ageya (meeting-houses) lining the Naka-no-chô, the main street. Although the main street is six blocks long, there are no divisions in the saiken to indicate where one block ends and another begins. |

|

Pages 5-6: More teahouses and ageya. Blank spaces probably represent empty shopfronts or shopfronts that are not teahouses or ageya. |

|

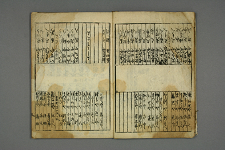

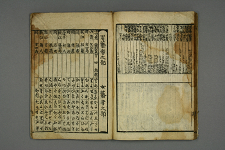

Page 7, on the right: The end of the street and the few teahouses located that far into the Yoshiwara. Page 8, on the left: The head of the Edo-chô It-chô-me, the street of high-class brothels that was the first right inside the main gate. The street name is written down the center of the street, beside the small image of a gate. Because the houses at the entrance to the street were large and high-ranking, each gets a full half-page to itself. Smaller houses get quarter-pages or a sixth of a page. The catalog of brothels proceeds street by street through the Yoshiwara, with the head of each street marked with a gate and the street name. The brothel listings look more or less like the ones on page 8, until you reach pages 45-46... |

|

Pages 45-46: This is the end of the Kyô-machi Ni-chô-me, the last street on the left of the main street. The regular houses with crests and courtesan rankings give way to small houses with nothing but a house name and a proprietor's name (at the bottom) and the names of the women working there (at the top). There are one to nine women working at each house, and all are so low ranking that they have no aijirushi. The small-house listings look sufficiently unlike regular house listings that it's easy to be thrown by them. However, these are legal, licensed brothels... just not very good ones. |

|

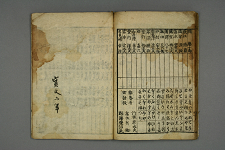

Page 47, on the right: The end of the small-house listings for the Kyô-machi Ni-chô-me. Page 48, on the left: Listings of male and female geisha. In the top two rows, the male geisha are listed by house and personal name, all written in kanji as befits male dignity and learning. The female geisha, in the bottom five rows, are listed by personal name only, spelled in the simpler hiragana script as befits women's simpler names and humbler learning. Most names are listedtwo to a cell, indicating pairs of geisha who were professionally partnered. Geisha were required to attend customers in pairs to discourage them from prostitution, so it made sense for women who worked well to gether to pair off. Later saiken place each female geisha's name in its own cell, but comments by Seigle indicate that there is a way to determine which geisha are partnered with which. I am not aware of how this is done. |

|

Page 49, on the right: More names of male geisha along the top and female geisha along the bottom. I have not translated the text in the lower left corner of the page. Page 50, on the left: Untranslated. |

All images © Waseda University All images © Waseda University |

Page 51, on the right: Names of another type of entertainer, (新改? 無? 宿?) untranslated. The names are probably all male. Page 52, on the left: I wish I knew. The top row is labeled differently than the bottom row. In the bottom left corner of most cells is a price. This listing continues until page 56, the end of the saiken. Top header: *** *** 戸 本? 町筋北 Top subhead: ** ** 堂 蔵? 梭? 目 録? Bottom subhead: Tsutaya Shigesaburo (蔦屋重三郎) [Name of the book's publisher] |

References

Cecilia Segawa Seigle's Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan has a short but informative section about reading saiken. The information is summarized online by another writer here.

Allan Hockley's discussion of Yoshiwara saiken, on pp. 92-96 of The Prints of Isoda Koryūsai: Floating World Culture and Its Consumers in Eighteenth-century Japan, and his analysis of existing saiken, on pp. 96-117, fill in some of the blanks left by Seigle. Conveniently online at Google Books.

The Japanese Wikipedia page on Yoshiwara saiken 吉原細見, for those who can read Japanese.

Updated 2/5/2015

Issendai.com

Issendai.com