Everyone drools over Turkish silks–with good reason. And there were silks aplenty in the wardrobes of 16th-century Istanbulites, even those of modest means. But the workhorses of the Ottoman wardrobe were cotton, wool, and cotton-silk blends.

Cotton • Wool • Miscellaneous • Silk • Furnishing Fabrics • Sources

A note about fabric names: Towns and regions specialized in not just different types of fabric, but specific variations on a type of fabric. For example, a city might be known for a particular brocade pattern. Everyone knew that pattern came from that city, so it made perfect sense to name the fabric after the city. But, because the Ottomans were bastards who existed solely to make textile researchers pull their hair out, no one wrote down the details. The result is dozens of “ghost” fabrics whose names we know, but which we couldn’t recognize if their anthropomorphic avatars slapped us in the face.

To avoid the worst of the confusion, I’ve listed only ghost fabrics that appeared in the estate records I studied.

Cotton and Cotton Blends

Alaca may be a cotton-silk mixture, if “alaca” isn’t a color reference. The other meaning of alaca is “brightly colored,” “multicolored,” or, by the 18th century, “striped.” The estate records contain a few “alaca keçe,” alaca felt mats, one alaca kirpas (cotton cloth), and several garments made of alaca kemha (brocade), but the rest of the many, many items labeled as alaca mention neither a color nor a fabric. That suggests that alaca was both a type of fabric and a pattern or patterns that needed no further color description.

Astar was a type of cotton cloth. In an 1802 source, it was used for linings. [link] Today it refers to three grades of muslin used for turbans and underwear.

Bez was a generic term for cloth, usually cotton but sometimes linen. Bez panbuk (pamuk) is definitely cotton.

Bogasi (or boğası) was a high-quality cotton twill used both as the main fabric for ordinary garments, and as a lining for grander garments. In the late 15th century, boğası was dyed and polished [link]–that is, run through a press to give it a smooth, shiny finish–so it may have been affordable, but it wasn’t drab.

Destâr was a very high-quality tülbent (itself a very fine cotton cloth) used for turbans. It was also used for handkerchiefs, women’s headcloths, and fine gömleks,1 among what were doubtless many other uses.

Kutni or kutnu was a mixed-fiber cloth with a silk weft and a warp of cotton, linen, cotton/silk, linen/silk, or silk.2 As you can see from the photo of Sultan Ibrahim’s kaftan, kutni was a glossy, satin-weave fabric, an attractive budget alternative to atlas (satin).

Kutni is best known as a striped fabric, which complicates the picture of 16th-century fashion. Kutni was a popular fabric, especially for kaftans and zıbıns. Stripes were not popular. Was 16th-century kutni not striped?

Unfortunately, the estate records aren’t much use in answering the question. Most of the kutni garments aren’t described in detail; two are medium blue, one is green, and one is listed as “kaftan sâde kutnî.” If this is a misspelling of “kaftan-ı sâde kutnî,” it means “kaftan of plain kutni,” which suggests there were other, non-plain kutnis around. However, a patterned fabric would cost more than a plain one, especially since easy-to-weave stripes weren’t in style, and kutni was affordably priced. (Ironically, the kaftan of plain kutni was among the more expensive kutni garments.)

Alternatively, were stripes popular at a social level that wasn’t depicted in extant miniatures? Tempting, but questionable. Court artists didn’t shy from drawing the rags of the beggars’ guild, and neither did bazaar painters. Why would they avoid drawing the distinctive dress of people whose clothes were merely unfashionable? European artists, who weren’t constrained by local concepts of fashion, would have found striped clothes irresistible. They didn’t draw people dressed in stripes either. The unavoidable conclusion is that in the 16th century, kutni, a fabric famed for its complex striped patterns, simply wasn’t striped.

In the estate records, kutni is used mainly for kaftans and zıbıns, ranging from 70 to 500 akçes and averaging 293 for kaftans and 114 for zıbıns. That pushes the cost of kutni very slightly toward the nicer end of affordable.

Muhaddem or mukaddem was similar to kutni, but for reasons unknown, was used almost entirely for belts.3

Penbe (modern pembe) was the generic term for cotton.

Tülbent was a fine, gauzy cotton whose name is the root of the word “turban,” and which was used mainly for making, yes, turbans.

Yemeni is something of a mystery fabric at the moment. By the 18th or 19th century it was a light cotton, sometimes a chintz, but in the estate records it was used mainly for soft furnishings, wrapping cloths, hand towels, and the like, so it must have been fairly substantial.

Wool and Wool-Like Fibers

Aba was a coarse, cheap wool often used for making a type of robe called an aba.

Yellow çuka coat, first half of the 17th century [source]

The best çuka was imported from Europe, with English broadcloth (“Londura çuha”) near the top of the list. And as an imported cloth, it was costly; in the estate records, an ell of çuka cost an average of 170 akçes, roughly as much as kemha (silk brocade). But perhaps only the more expensive types of çuka were inventoried by the length, because garments of çuka ranged the gamut from Mustafa Reis b. Yusuf’s 1,165-akçe purple çuka ferace, through Süleyman Beşe b. Yakub’s 500-akçe purple çuka yelek, to a variety of jackets, feraces, and zıbın appraised at the eminently reasonable price of 200 to 300 akçes, to a pair of şalvar worth 75 akçes and hats valued at 21 akçes the pair.

Çuka was also the name of an overcoat, which was presumably made of wool broadcloth at one time or another, but by the time of the estate records could be made of other fabrics as well.

Karziye, or kersey, is a light woolen cloth that was originally imported from England, but came to be produced locally. It wasn’t beaten as heavily as English broadcloth, so unlike çuka, the weave was visible on both sides.4

Keçe, kebe, and the rarer term nemed are all felt, though sources are maddeningly vague on the difference between the three. (We do know that kebe was thicker than keçe.5) Felt could be brightly colored–estate records are full of felt floor mats in red and yellow, as well as more somber green, blue, purple, and black–or left its natural color. Descriptions of escaped slaves’ felt garments are among the few references we have to people wearing gray clothes.

Some types of felt overcoat, like the Yanbolu kebe (see below), were sought-after, but in general, felt was considered inferior to woven cloth. Felt trousers and inner jackets were laborers’ clothing. A post-period Ottoman Turkish dictionary equates “clad in felt” with “poor.”6 Even in furnishings, felt was inferior: felt blankets were more commonly used for horses than for humans, and felt floor coverings made fine rug underlays, but they weren’t what you displayed in the best room unless you didn’t have a proper woven carpet.

Muhayyer is a very cheap mohair fabric. Of the 14 muhayyer garments in the estate records, there were four ferace, six benevrek (a type of men’s trousers), two fistan (a skirt or skirt-like garment worn by non-Muslims), one yelek, and one kaftan, all incredibly cheap.

Sof is also mohair, but soft, top-quality luxury mohair.

Tiftik is Angora, aka mohair. It was very sturdy, since it was used mainly for making rugs and curtains; the only tiftik garment in the records is a belt. Tiftik may be a description of fiber content rather than a textile name.

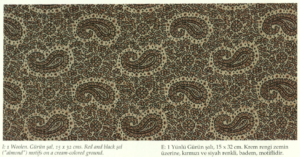

Şal is fine wool woven into the kinds of patterns that still adorn traditional Indian shawls. The best şal was imported from India and Persia, but eventually Turkish weavers took up the challenge. According to Hülya Tezcan, “Ottoman şals are virtually indistinguishable from those produced elsewhere and, indeed, one of the features of şal is that its fundamental patterns remain faithful to their roots regardless of the country in which the cloth is woven.”7

The most common pattern was the “almond” (badem) pattern, featuring alternating rows of small paisley-like motifs. It was so characteristic of şal that even when it was woven into other fabrics, it was called “şal pattern.”8

There was only one piece of şal in the estate records, marked as old and very cheap. However, there were also a few pieces described as bademî, the adjectival form of “almond,” suggesting that even if most people couldn’t afford şal, they could still afford fabrics in şal pattern.

Yanbolu is a type of felt made in the Rumelian town of, yes, Yanbolu.[link] It was used mainly to make kebe, variously defined as carpets or as horse blankets, but it could also be made into good-quality overcoats.

Miscellaneous Fibers

Dimi may be fustian, a heavy cloth made of cotton, linen, wool, or a mixture of fibers.

İplik is either yarn/thread, or linen. Unclear.

Kenevir is hemp.

Keten is linen, a relatively rare fabric.

Kürk is fur, used to line overcoats and, occasionally, winter kaftans. The Ottomans used an impressive range of furs:

- Âhu, gazelle

- Ayı, bear

- Çakal, jackal

- Cılkava, the throats of wolves

- Kakum, ermine, a summerweight fur (didn’t appear in the estate inventories)

- Keremun or tay, foal (didn’t appear in the estate inventories)

- Kurt, wolf

- Kuzu, lamb

- Samur, sable, a winterweight fur

- Sansar, beech marten

- Sincab, gray squirrel, worn in the spring and late autumn

- Tavşan, rabbit

- Tilki or elma, fox (didn’t appear in the estate inventories)

- Vaşak, lynx

- Zerdeva, pine marten

The Ottomans made a distinction between different parts of a fur. For example, the throats of wolves and foxes were sought after, so much so that furs made of sewn-together wolf throats had their own name, cılkava. The head, neck, back, and shanks and feet of martens could be used separately; so could the shanks and feet of wolves, lynxes, and sables, and the bellies of leopards.[link]

Post (or postin) is fur or leather.

What You’ve Been Waiting For: Silk

Scholars have labored for centuries over the different types of silks, defining what counts as seraser, what is serenk, and what is merely kemha, what separates çatma from lesser velvets, how to separate the avalanches of glorious fabrics into organized streams. This is valuable from the viewpoint of modern scholars, who need a precise shared vocabulary. It’s less useful in answering the question, “What did the estate-writers mean when they said Mihri Hatun’s kaftan was made of kemha?”

İpek is the generic word for silk, but people usually used one of the dozens of more specific words for types of silk.

Atlas is a highly prized silk or silk-and-cotton satin. One modern scholar calls it the standard fabric for aristocrats’ clothes, an observation borne out by the estate records. Well-off people may have preferred brocades or gold-shot silks, but they filled in the gaps in their wardrobes with atlas.

In atlas, poets found a rich source of metaphors. It was likened to the sun’s rays curtaining the sky at dawn. The sun-dappled grass of a garden was compared to green atlas embroidered with gold çintamani. Because of its smoothness, fineness, and rich color, red atlas was compared to rose petals. The closed bud was red atlas folded away in a chest, and the opening of the bud was like taking the silk out of the chest.9

Bağdâdî is a wildly expensive fabric that appears in the estate records without explanation. Given the cost, it was definitely silk, possibly with gold or silver threads, possibly brocaded; given the name, it was made in Baghdad.

Bürümcük is a plain or self-striped white gauze that was considered particularly suitable for gömleks and underwear. In an early 17th-century market price list, bürümcük was even listed as being sold by the gömleklik, “enough fabric to make a gömlek.”

The best and softest bürümcük was made entirely of raw silk, but it could have a warp of cotton, linen, wool, or a blend of fibers. Mixed-fiber bürümcük was sometimes called helalî or hilalî.10

Çatma or çatma kadife is the finest type of velvet: brocaded silk velvet with a raised design, sometimes woven with gold thread. Once upon a time Turkish artisans excelled at making çatma, but by the 16th century, Italian weavers had far outstripped them.

Dârâyî is an affordable-but-not-cheap light silk. In the estate records it was used for garments that were meant to be seen–kaftans and zıbıns.

Dibâ is a heavy, glossy silk brocade of such high quality that in period, it was restricted to the palace. However, late in period and/or shortly after period, the living standard had risen enough that wealthy commoners were starting to own modest quantities of dibâ. [link]

Hâre is an expensive “marble-like wavy fabric” that we probably know as moire silk or watered silk. It was often described as telli, “woven with metal threads.”

Kadife is velvet. There were many types of velvet, but if a fabric is described only as kadife, it was probably single-color, single-pile velvet.

Kemha is a heavy silk brocade of a type referred to by modern scholars as lampas.

Kumaş is the modern Turkish word for fabric, but based on the fabrics listed under the “Kumaş” heading in the 1600 and 1624 official price lists (narh defterleri) for Istanbul, kumaş was a generic term for any silk or silk blend.

Serâser is a rich brocade with a ground of metallic threads. This was the richest type of fabric the average obscenely wealthy Istanbulite owned at the end of the 16th century.

Sirenk, more commonly spelled serenk, is a budget brocade in which the gold threads have been replaced by yellow silk threads.11 There were only two instances of serenk in the records, possibly because brocades of that type were included under one of the other terms.

Tafta is taffeta, a plain-weave silk with a crisp hand.12 Because of its combination of luster and durability, it was in demand not only for garments, but for cushions, quilts, and other soft furnishings.

Tafta (and taffeta) can be smooth, or it can be slightly ribbed, like fine Dupioni silk. The best extant examples of 16th-century tafta are the facings of several kaftans in the Topkapi collection, some of which display this fine texturing.

Tafta was one of the more affordable silks in 16th-century Turkey. However, in the estate inventories, the cost of garments made of tafta varies wildly, from two zıbıns worth 46 and 43 akçes, to a 202-akce gömlek of Egyptian tafta, to a 500-akçe came of printed red tafta, to an utterly decadent 600-akçe gömlek of white tafta with buttons. One lady with 500 akçe to waste even made her underwear out of tafta.

Ümmî bt. Sinan, a lady of great wealth whose wardrobe was a wonder to behold, had two quilts of staggeringly rich serâser silk, and naturally the sheets that went with them were tafta. Not plain tafta, though–ugh. One sheet was red and “münakkaş,” decorated–either patterned or embroidered–and had buttons, possibly to attach it to the underside of the quilt. (Sheets were usually pinned to the underside of the quilt.) The other sheet was medium blue, and also buttoned. Each quilt-and-sheet set cost 3,000 akçes.

And yet, tafta by the ell wasn’t expensive. Fâtıma bt. Süleyman owned three ells of green tafta that cost 50 akçe, or 16.67 per ell; Mahmud Bey b. Perviz Bey’s four ells of tafta cost only 40 akçe, or 10 per ell. A bale or loom-length of tafta owned by Sâliha bt. Mehmed cost 290 akçe. We don’t know how long the loom-length was, but three loom-lengths of cotton cloth elsewhere in the records were 10 ells, 10 ells, and 8 ells long. If the tafta loom-length is comparable, it cost only 29 to 36 akçes per ell–not much more expensive than the cotton loom-lengths. If the estate records aren’t misleading, tafta may have been valued less on its own merits and more as a base for embroidery and other forms of decoration.

Vale or valâ is a type of light plain-weave silk. According to one source, vale is identical to tafta, except that vale “was put through a kiln after being woven.”13 I’ve had no luck in finding any references to putting silks through a kiln, and I’m not committed enough to bake my own silks, but I suspect kilning softened the tafta, possibly weakening the silk but making it more pleasant to wear against the skin.

Vale, like tafta, was an affordable silk. And like all affordable silks, it got made into underclothes. All four of the vale garments in the estate records are luxurious, rather expensive underpants (don).

İbrişim is pure silk thread that was used for weaving belts.

Fabrics Used for Furnishings but Not Clothes

Beledî is a sturdy cotton fabric, often locally made and/or homespun, that was used for furnishings. Its natural color was beige, but it could be colored. Post-period it was often mentioned as being red, white, black, or patterned in those colors.

Havlu is the napped cotton cloth now known as Turkish toweling. Then as now, it was used mainly for towels and washcloths.

Hindî, imported Indian cloth, is something of a mystery at the moment. It was inexpensive, and was used for pillows and quilts.

Kirpas (also kirbas, kirbaz) is a heavy canvas of cotton, linen, or hemp. One source refers to it as sailcloth. In the estate records, it appears only in unsewn lengths.

Velense is a thick wool with a nap on one side that was used for blankets. It was also the word for blankets made of velense.

Sources

The Textile Market in Istanbul and Bursa in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: An Introduction, by Miki Iida-Sohma, has some useful, if sometimes post-period, fabric definitions.

- See Ismihan Hatun‘s “pirâhen-i destâr.” Pirâhen was the Persian word for “gömlek.”

- Reindl-Kiel, Hedda. “The Empire of Fabrics: The Range of Fabrics in the Gift Traffic of the Ottomans.” Inventories of Textiles – Textiles in Inventories: Studies on Late Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture, eds. Thomas Ertl and Barbara Karl. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017. P. 162. [link]

- Reindl-Kiel, pp. 153-154. [link]

- Özgür KOLÇAK, OSMANLILARDA BİR KÜÇÜK SANAYİ ÖRNEĞİ: SELANİK ÇUHA DOKUMACILIĞI (1500-1650), p. 74. [link]

- Tezcan, Hülya. Atlasar Atlası, Cotton, Woolen and Silk: Fabrics Collection. Yapı Kredi Collections – 3: Istanbul, 1993. P. 24.

- The word in question is “nemed,” which in the 16th century was a felt garment that appears repeatedly in court records from the semi-rural town of Üsküdar, near Istanbul. The Ingilizce Osmanlica dictionary defines it as “Felt; felt cloth”, and one of its derivations is “Clad in felt; i.e., poor.”

- Tezcan, Hülya. Atlasar Atlası, Cotton, Woolen and Silk: Fabrics Collection. Yapı Kredi Collections – 3: Istanbul, 1993. P. 26.

- Ibid.

- Öztoprak, Nihat. “Divan Şiirinde Giyim Kuşam Üzerine Bir Deneme,” Divan Edebiyatı Araştırmaları Dergisi 4, İstanbul 2010, pp. 108-109.

- Tezcan, Hülya. Atlasar Atlası, Cotton, Woolen and Silk: Fabrics Collection. Yapı Kredi Collections – 3: Istanbul, 1993. P. 28.

- Tezcan, Hülya. Atlasar Atlası, Cotton, Woolen and Silk: Fabrics Collection. Yapı Kredi Collections – 3: Istanbul, 1993. P. 34.

- Tezcan, Hülya. Atlasar Atlası, Cotton, Woolen and Silk: Fabrics Collection. Yapı Kredi Collections – 3: Istanbul, 1993. P. 28.

- Tezcan, Hülya. Atlasar Atlası, Cotton, Woolen and Silk: Fabrics Collection. Yapı Kredi Collections – 3: Istanbul, 1993. P. 28.