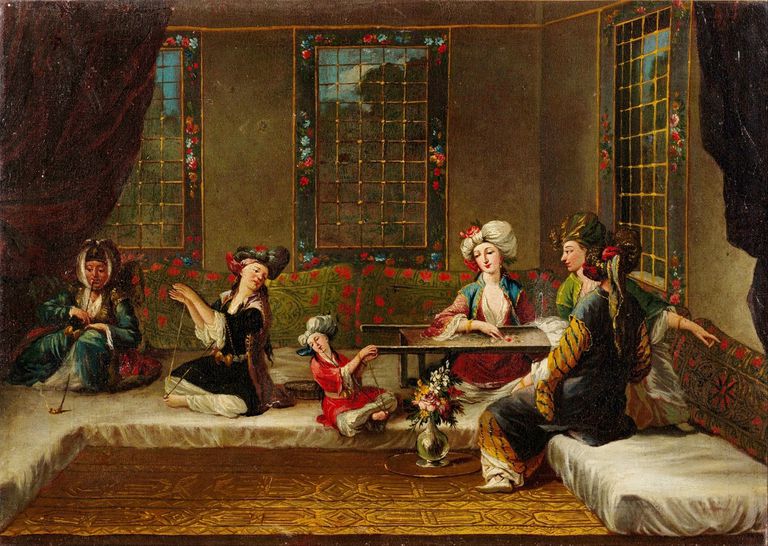

For centuries, outsiders have envisioned the Turkish house as a man’s world, a lushly carpeted, cushioned paradise with, off to the side, a sort of fancy rec room where they keep the women.

Probably naked.

Now switch up the scene a little. Imagine you’re the man at the right, with your hookah in your lap and your concubine clad only in pearls spread out before you. Now imagine that the dark-haired woman seated at your side is dressed.

And she’s your mom.

That was half the reality of the Turkish harem. It wasn’t the part of the house where the pretty, sexy girls lived. It was where all the women lived. Your wife, your concubines, your female servants and slaves, your daughters, your bitch sister who couldn’t stay married, your impoverished widowed aunt, your mom. You try getting up to exotic fun sexytimes with your mom in the next room.

The other half of the reality is that you lived in the harem, too.

The harem wasn’t a separate part of the house for women only. It was the family home. The root of the word is the Arabic haram, “forbidden,” but it’s better understood as… When you’re at a house party, you know how you don’t have any qualms about wandering through the living room, dining room, and kitchen, but you don’t go upstairs? That’s because the part of the house with the bedrooms is haram.

In 16th-century Turkey the entire house of a Muslim family was haram. People guarded their family’s privacy closely. It wasn’t merely a question of preventing other men from seeing your wife and daughters, it was a matter of keeping the intimacies of family life safe from the outer world.

However, the underlying principle was still female modesty. From childhood on, a Muslim woman covered herself in the presence of any man who was eligible to marry her–that is, any man who wasn’t her father, grandfather, brother, uncle, nephew, father-in-law, husband, son, or grandson. Muslim societies have interpreted the “covering” requirement in many ways; in the region of 16th-century Istanbul, women covered all their hair and all of their faces except for their eyes,1 and they obscured the lines of their bodies with a long, unfitted, loose-sleeved coat called a ferace (feh-rah-JEY). It was hot, it was cumbersome, it was utterly unsuited to housework. Rather than obliging women to go about in veils and ferace all day long, the culture declared women’s workspace, the house and courtyard, to be private areas accessible only to women and the men who were allowed to see them uncovered.

This was possible partly because the Ottomans preferred to separate work from home. Unlike in Europe, where many men worked out of their houses, most city-dwelling Ottoman men had workspace in the marketplace or khans (inns). A well-to-do family might build an outer courtyard that was male workspace, and if the family did really well and the men needed to receive clients or entertain guests, they might add a reception room (selamlik) specifically for male guests. (It was often over the stables, like an elegant version of the modern man-cave over the garage.)

That was the closest the average family got to separate quarters for men and women. Even then, the man of the house probably spent most of his non-working time in the haram part of the house, doing exotic, sexy things like eating dinner and fixing the coffee grinder.

So what was a real Ottoman Turkish harem like? It was a house of one to three rooms, a little piece of courtyard, maybe a veranda. Children ran in and out of the rooms, shepherded by your mother or sister or maybe a servant if you could afford one. Your wife cooked dinner in the corner of the courtyard. When it was done, everyone sat in a circle on the veranda or in one of the rooms, and you wife set the dishes down one at a time in the center for everyone to share. In the evening you sat and chatted on the veranda in warm weather, or around the fire in winter. At night your wife pulled mattresses and bedclothes from the cabinets and spread beds on the floor, and you went to sleep surrounded by your family. Exotic? Nope. But heavenly? Perhaps.