Underwear

A man stripped to his underwear. [source]

Don were loose but not voluminous, about as baggy as sweatpants, and they tapered at the ankle to a hole just large enough to get the foot through. Full-length don were a little long, which is necessary with the method of pants construction the Ottoman Turks used. Instead of hugging the wearer’s butt and pulling down the rear waist when the wearer sits, the pants are loose through the butt and tug up the back of the legs when the wearer bends over. The more junk in your trunk, the higher up your shins the pants rise. Although the Ottoman Turks didn’t have any issues with women showing leg, it’s annoying to constantly have your pants hike up your legs, especially when the tapered cuffs get caught on your shins and you have to yank them down. The solution: Make the pants long enough that at maximum bend, the cuff stays in place.

The downside is that even with the smallest possible opening that will still let you get your pants on over your heels, the back of the cuffs are liable to fall under your heels when you walk. The effect is visible in all the images drawn by Ottoman Turks; it was a feature, not a bug.1

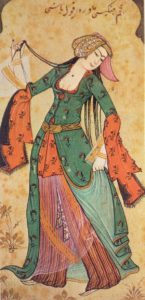

Don were gathered shut with a linen uçkur (uch-KUR), which is usually translated “drawstring” but which was more like a sash. The ends of an uçkur could be embroidered, like the uçkur of the man to the right. By the 17th century, women’s uçkur were exuberantly decorated and dangled enticingly below the hems of their zıbıns, but in the 16th century they were more restrained affairs that were tied modestly out of sight. Nevertheless, women often owned more uçkur than pairs of don and trousers combined.

There is one extant pair of don in the Topkapi Palace collection, a knee-length pair made of a silk gauze called bürümcük (bew-rewm-jewk) that was considered particularly suitable for undergarments.

The palace label describes the underpants as “çakşır,” a much later definition of the term. In the 16th century, underwear was don, trousers were çakşır, and şalvar was a style of men’s çakşır, but by the early 18th century, the standard word for trousers was şalvar, and çakşır was a term for underpants. Turkish costume scholars tend to use the terminology of the 18th century, thus the misleading label.

Support Garments

…Didn’t exist. There are at least a dozen period pictures showing women with their tops unbuttoned, and not a one of them shows so much as a hint of a breastband, much less a more complicated garment.

Modern costumers have observed that if you cut the zıbın (short underjacket) snugly, it can provide some support. As appealing as the hypothesis is, I doubt it was standard in the 16th century. 16th-century clothes were close-fitting, but not tight; the explosively bosomy look we SCAdian ladies adore is an 18th-century anachronism yoinked from an era when ordinary women’s clothes were skin-tight and palace beauties’ tops were cut so small that they couldn’t have buttoned them if they wanted to. The 16th-century woman who unbuttoned her top seductively wound up with a modest V that didn’t tug open noticeably across the chest. Most women’s zıbıns simply weren’t tight enough to provide bust support.

That said, some of the ladies in the 1610 Album of Ahmed I are wearing clothes tight enough to show tug lines across the front, and their tops gap slightly across the chest. The average woman may not have dressed so racily, but if you want to try sewing a supportive zıbın, there is some, um, support for support.

An Illustrated Guide to the Layers Çakşır | Trousers

- In the mid-17th century a new cut of trousers called çintiyan came into style, and one gentleman made his male servants wear them because they exposed the young men’s heels sexily when they walked. (Karababa, Eminegul. “Investigating early modern Ottoman consumer culture in the light of Bursa probate inventories.” Economic History Review, 65, 1 (2012), pp. 210-211.)