[in progress]

How were 16th-century gömleks made? Persian-style, with the skirts gathered at the hip? Egyptian-style, with the underside of the sleeve made in a piece with the side of the shirt? Using rectangular construction, like early European tunics? Or a mashup of Egyptian and rectangular tailoring with a Turkish twist, like 18th- and 19th-century gömleks? All these methods produce gömleks that can pass for the garments we see in art. Because only the skirt, sleeves, and neckline of the gömlek show in drawings, we have no idea how the all-important torso of the garment was tailored, so we can’t rule out any method. And because there are no extant period gömleks–

Actually, there are extant period gömleks. Almost a hundred of them.

Because there are no extant period gömleks that aren’t the sultans’ special magical shirts–

There is one.

Because there are no extant period gömleks that aren’t the sultans’ special magical shirts that I’ve heard of—

One and a half, counting the gömlek from the first half of the 17th century.

Okay, you’ve flummoxed me. Explain.

When we look for clues to the cut of 16th-century gömleks, we pass over the sultans’ talismanic shirts (tılsımlı gömlekler) because–well, look at them. They’re extraordinary. Not only are they works of art, they’re religious objects. Who knows what rules they follow? They also don’t look like the gömleks we’re trying to recreate, shin-length and long-sleeved; if anything, they look like sawed-off, stunted versions of “real” gömleks. It’s natural to write off talismanic shirts as ritual garments and assume that everyday gömleks must be nothing like them.

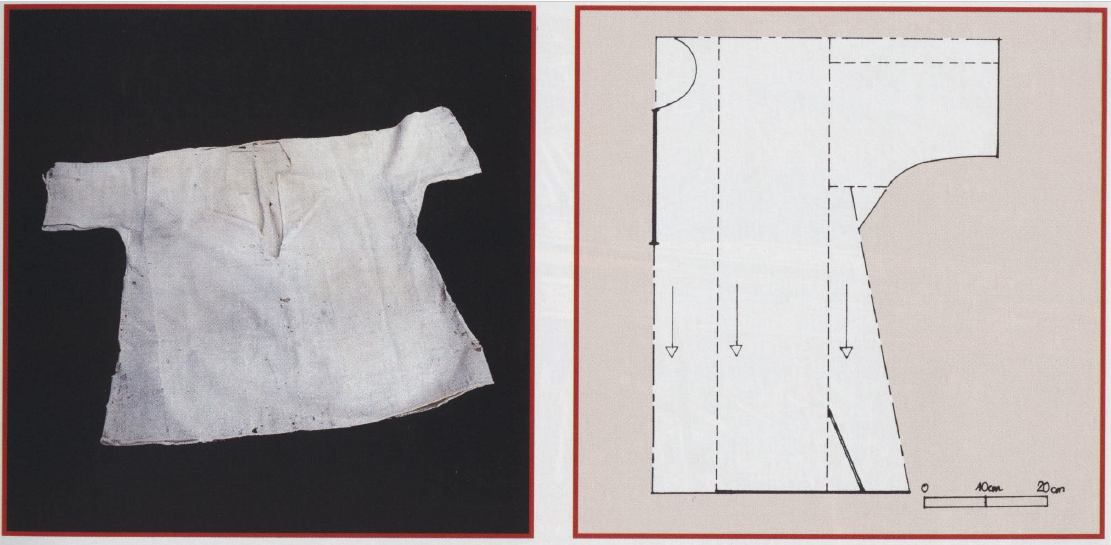

But preserved in a Sufi lodge is the gömlek of a dervish who died in 1576. It’s short and short-sleeved, like a talismanic shirt. And it’s sewn from many narrow strips of cotton, like it was assembled from the leftovers of a more important project. The Sufis were ascetics who adopted working-class clothes as their habits, and the dervish’s gömlek is unquestionably the inexpensive, inelegant undershirt of a man who couldn’t afford to put money into a garment no one else would see.

It’s also unquestionably the same garment as the talismanic shirts.

We’re not used to seeing this truncated form of the gömlek because it was designed to be unseen. Ankle-length kaftans were a status symbol; plenty of men, from laborers to page boys to elegant young gentlemen who could afford to go day drinking, weren’t high-ranking enough to wear kaftans. Instead, they wore hip-length jackets, which were too short to cover a full-length gömlek. Rather than stuffing their gömlek skirts into the already enormous seats of their trousers, men wore short gömleks that showed only at the throat, if at all. We’re left to deduce the existence of their gömleks from the fact that not wearing a shirt meant all your good (that is, unwashable) clothes smelled like eau de armpit, and from the surfacing of garments like Şeyh Şaban-ı Veli’s short gömlek.

Talismanic shirts aren’t exceptional garments, they’re exceptionally beautiful versions of common garments. Millions of men across Turkey pulled on something just like them every day.

So if the shape of talismanic shirts is the same as the shape of ordinary short gömleks, is it possible to deduce the construction of ordinary gömleks from talismanic shirts? I think so. The basic principles of rectangular construction are universal, and though most 16th-century court garments aren’t even remotely rectangular-tailored,1 the talismanic shirts, Şeyh Şaban-ı Veli’s gömlek, and other clothes belonging to Şeyh Şaban-ı Veli are all rectangular-tailored.

The Sufis preserve important dervishes’ clothing in their lodges. Some of it is suspect–like the 13th-century mystic Rumi’s ferace in exquisite 17th-century style2–but some of it is convincingly

There are two extant men’s gömleks, one long and one short, neither from the Topkapı collection and therefore not widely known. I’ll start with the short gömlek, since it shows the rectangular piecing most clearly.

The gömlek is made of strips of fabric so narrow, they’re almost scraps.

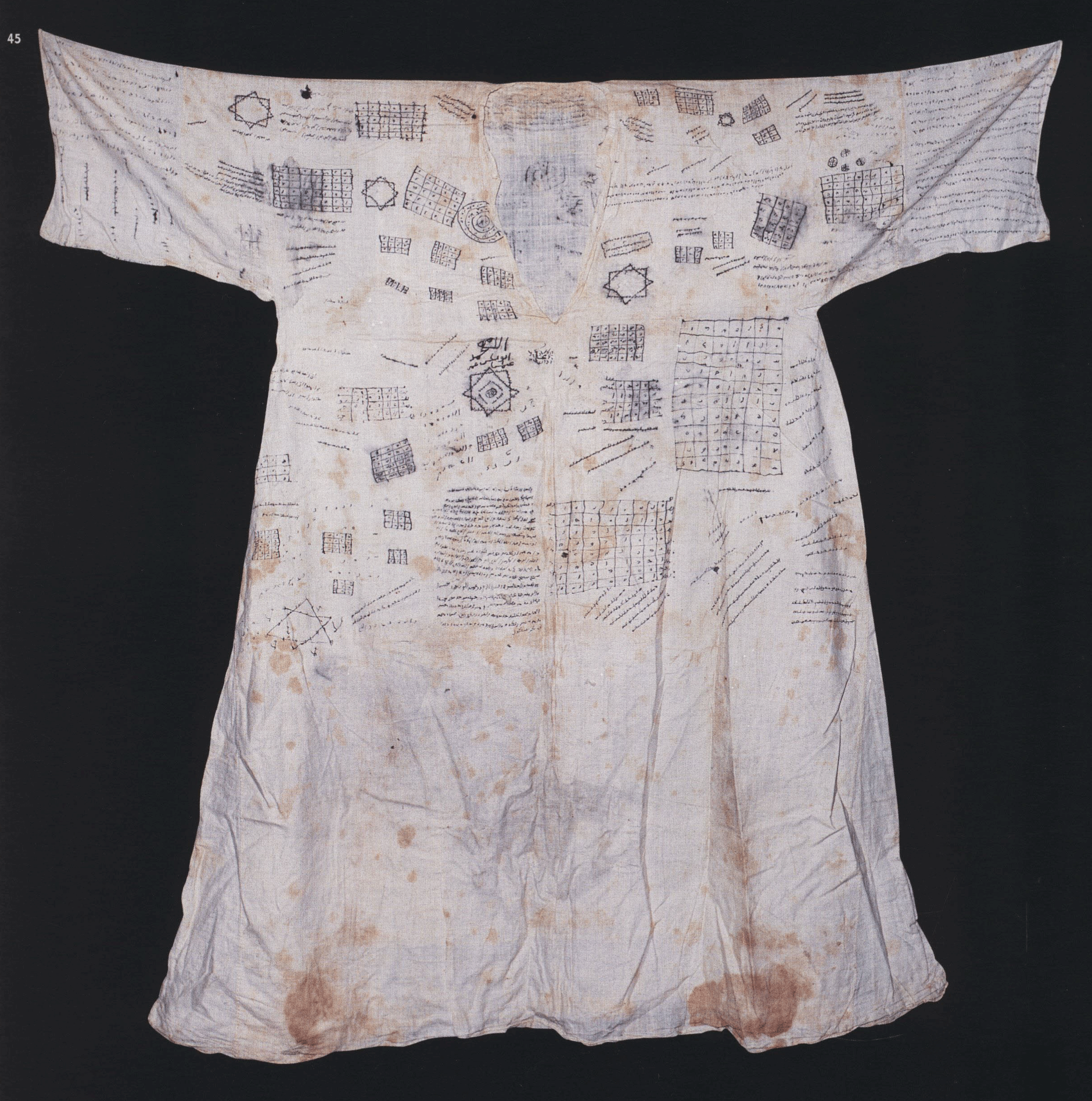

The second gömlek probably dates to the first half of the 17th century. It’s covered with inked diagrams and inscriptions, making it a working version of the glorious gilded and embroidered talismanic (tılsımlı) gömleks in the Topkapı collection.

Talismanic gömlek of Aziz Mahmud Hüdai, one of the most famous saints of the Ottoman Empire, who was born in 1541 and died in 1648. Click to see full-size.

The body of the gömlek is cut from a wide length of cotton, with the seams falling about two-fifths of the way down the sleeves. The skirts are cut in an A-line from the armpits, with vertical seams in line with the sleeve seams. This layout method is the same one used for the extant kaftans in the Topkapı collection: Center the shape of the garment on the fabric, cut it out, and fill in the missing bits at the edges with waste fabric.

Extant 16th-Century Tılsımlı Gömleks

With the exception of the two gömleks above and a handful of children’s shirts in the Topkapi collection, all the known 16th-century gömleks are men’s talismanic gömleks.

Dated 1583, auctioned by Sotheby’s: Cotton, short, short-sleeved. Front and back are plain rectangles, with the sleeves and side flares added to the edges.

Dated 16th century, auctioned by Sotheby’s: Cotton, short, very short sleeves. The underside of the sleeve is a curve, not an angle. The sleeve and side flares are all one piece of fabric, which is sewn to the sides of the central panel.

Dated 16th/17th century, auctioned by Sotheby’s: Cotton, mid-length, short-sleeved. The front is slit all the way down, a style seen in other shirts. The front and back are plain rectangles, with sleeves, side gores, and underarm gusset sewn to the edges.

Gömlek | Shift Zıbın | Short underjacket

- The court tailors preferred the same construction method you used to make your first T-tunic. It produces fewer seams down the center third of the garment, allowing the display of unbroken expanses of brocade.

- Followers made their deceased leaders gifts of clothing, some of which was incorrectly recorded as belonging to the leader in life.