The hardest part of Turkish clothing is figuring out the layers. You’ve got long robes and short robes and bits poking out and layers on top and layers underneath and layers that must have been added just to make you tear your hair out, and which ones do you wear and what do they mean and aaaaaaaaaaaugh I’m going back to Italian ren.

But it’s easy. It’s really, really easy. 16th-century Ottoman Turkish women wore only a few layers, all predefined, with far fewer variations than their European counterparts. Once you know what a woman should be wearing, it’s child’s play to look at a picture and assign each visible piece to a garment.

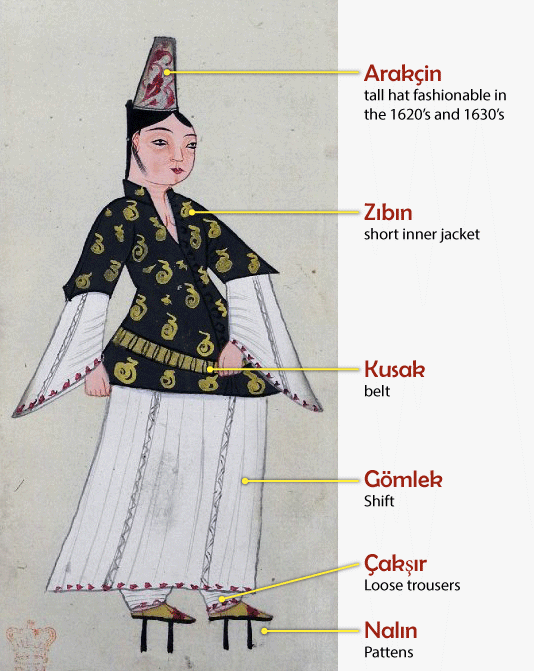

Let’s start with how women dressed at home. This outfit–minus the pattens–is the minimum a woman could wear to call herself fully dressed.

Pronunciation

Gömlek: like gurm-lek, but without the R

Zıbın: The dotless ı is a schwa, the amorphous vowel that’s represented by the O in “button” or the E in “raven,” so zıbın is pronounced something like z’b’n.

From the skin out, a woman wore trousers (don or çakşır), a long shift (gömlek), and a hip-length jacket called a zıbın. In modern terms, the trousers, gömlek, and zıbın are analogous to pants, camisole, and blouse.

There are a couple of variations for each garment:

- Trousers could be loose and plain (don—technically underwear, but women wore them as trousers), or fitted and made of showy fabrics (çakşır).

- Most women’s trousers were full-length, but a few women owned knee-length trousers, which don’t show in pictures.

- The gömlek could have angel-wing sleeves like the woman above, or extra-long, tight-fitting sleeves like the seated woman in the center of the picture at the top of this page. Angel-wing sleeves were by far the most common.

- Most women’s gömleks were long, with the hem varying between mid-calf and ankle depending on the fashion. However, occasionally women wore gömleks that were shorter than the zıbın, so they appeared not to be wearing a gömlek at all.

- The zıbın could be collarless, or have a small standing collar like the woman above.

- The zıbın could be sleeveless, short-sleeved, or long-sleeved.

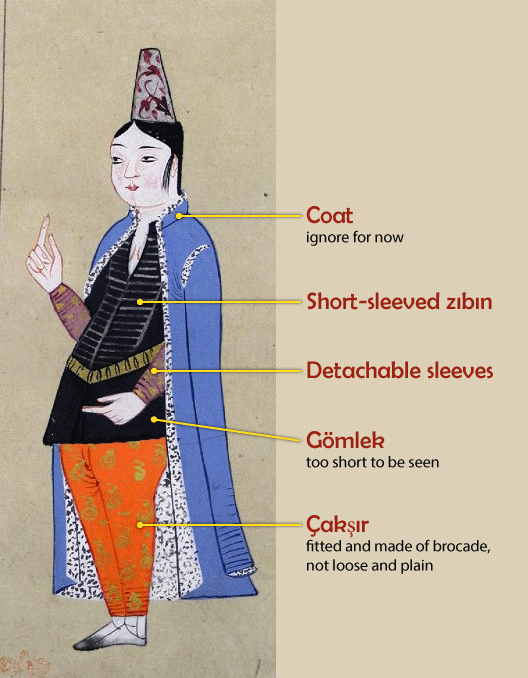

Short-sleeved zıbıns could be accessorized with detachable sleeves in a different fabric.1 This is a point that confuses the hell out of many people, because it looks like the woman is wearing another garment under her zıbın, but there’s no garment under the zıbın except the gömlek, but she’s wearing another garment and that garment doesn’t exist and aaaaaaugh where’s my Italian Ren.

This is what a woman in zıbın and detachable sleeves looks like:

The vast majority of images of women in at-home dress look like the two pictures above: short-sleeved zıbın, long gömlek, loose trousers. However, make a few changes, and a woman2 who’s wearing almost the exact same layers looks completely different:

Apologies for the coat. I know of only three pictures of women in short gömleks, and the other two are wearing kaftans.

When you’re faced with a picture that doesn’t match the usual silhouette, assume the woman is wearing the same layers, and work from there.

The zıbın is casualwear, at-home-wear, lounging-in-the-garden-wear, chopping-carrots-for-dinner-wear. If a woman planned to appear before anyone who wasn’t her immediate family, she added the formal layer of dress, a kaftan.

Kaftans, like zıbıns, could be collared or collarless, short-sleeved or long-sleeved. (But not sleeveless.) They varied very little in length, from slightly above the ankle to brushing the tops of the feet.

Because a kaftan covers the rest of a woman’s clothes and has few variations, it’s easy to pick the kaftan out of any ensemble. The potential confusion comes, again, from detachable sleeves. A kaftan could be worn over a zıbın with detachable sleeves; we also know, from extant garments in the Topkapı Palace collection, that sleeves could be buttoned into a kaftan. There’s no way to tell whether a woman in a drawing is wearing sleeves buttoned into her zıbın or her kaftan. If no other part of the woman’s zıbın is showing, it’s also not possible to tell whether her sleeves are detachable, or whether she’s wearing a long-sleeved zıbın. But, if a flap of her zıbın pokes out the front of her kaftan, a mismatch between the flap and her sleeves means her sleeves are detachable:

For warmth, women wore a variety of overcoats, from the (unnamed) full-length coat with hanging sleeves that the girl above has draped over her shoulders, to the tea-length kürdiyye, to the knee-length dolama, to the hip-length yelek. The kürdiyye and dolama don’t appear in pictures of women, though we know they owned them, and the full-length coat appears very rarely. The most common overcoat women are shown wearing is the yelek, a short jacket that could be sleeveless or short-sleeved and collared or collarless. A woman could wear it over her kaftan, or if she was at home, over her zıbın.

Note the position of the belt. The belt goes over the innerwear and under the outerwear. This never changes, so if you can’t tell whether a garment is a coat or a kaftan, look for the belt.

And now we’re done with the layers.

No, really. That’s it. Pants, shift, zıbın, kaftan, belt, overcoat.

Accessories? Accessories are all over the map. Hats go from pillbox-shaped to conical to cylindrical, and you put one veil over them and another around them and tie something else around them–or around your head, whatever, fashion is all about thinking outside the box. There are shoes that go inside shoes that go inside pattens. There are a dozen ways to tie a scarf-belt, and then they introduce belts made of leather or plaques and start designing buckles that a Texan would think were over the top. But regardless of the shape of the accessory, a woman always wore a hat, and a belt, and (usually) a pair of shoes. And also pants, shift, zıbın, kaftan, and maybe an overcoat.

One more point of interest is that there was no duplication of layers. A woman always wore one zıbın; she wouldn’t wear two, any more than you would wear two blouses or two sweaters. There was also no omission of layers. A woman wouldn’t wear a kaftan without a zıbın, any more than you would put on a suit jacket without a shirt. If an essential garment appears to be missing, it’s covered by the other garments; if it appears to be duplicated, then one of the elements actually belongs to another garment.

(Or is a pair of sleeves.)

So when you’re faced with a picture of a woman–or when you’re planning an outfit for yourself–remember: pants, shift, zıbın, kaftan, belt, overcoat. And you’re done.

Women’s Garb, Piece by Piece Don | Underpants