The most common type of footwear, for men and women alike, was a soft leather sock called mest or iç edik, slipped into a leather slipper called an edik or pabuç (or papuç, or babuç).

Mest/Iç Edik

Mest/iç edik were worn as indoor shoes. Not many have survived, but here’s a 17th-century mest inside its shoe:

Leather socks have a long history in the Middle East, and are still sold by specialty sellers under the name “khuffs” or “khuffain.”

Pabuç/Edik

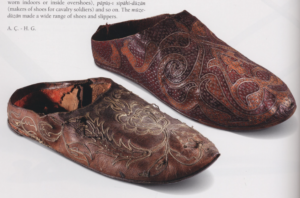

Pabuç were the 16th-century version of modern babouches, identical except for the decoration and the toe. Modern babouches often have sharply pointed toes, while 16th-century pabuç have rounded toes or only a very slight point.

Although extant pabuç have low backs, most art suggests that just as with modern babouches, the back was folded down and stepped on. This adds an extra layer of material under the heel, right where the sole is most prone to wear through.

It’s also inevitable. Speaking as one who’s spent much of the past year and a half in and out of house slippers, I can assure you: No matter how much you hate backless shoes, no matter how much you vow to preserve the backs of the lovely Japanese slippers your mother got you for Christmas, you will fold the backs down and tread on them. Slipping your shoes on and off repeatedly is a pain, pulling the soft, easily crumpled back of the shoes over your heels every time is a pain, and one day you will give in. The Ottoman Turks removed their shoes when entering their living/sleeping/entertaining rooms (oda), to avoid tracking dirt into the cleanest and most beautifully carpeted rooms in the house, so they had plenty of reason to make the process of taking their shoes on and off as easy as possible.

We’re short on 16th-century pabuç, but these are from the 17th century: