About Japanese Courtesans' Names

What's a Tayū? What's an Oiran?

The short answer: "Oiran" is a word for "courtesan" that became fashionable in Yoshiwara, the licensed pleasure quarter of Edo, in the 1750's. There were many ranks of courtesans, whose titles and popularity shifted constantly, but to give you a sample of the rankings, this is the list of oiran-level ranks from a Yoshiwara guidebook in 1792:

Tayū

Kōshi

Yobidashi Tsukemawarashi

Sancha

Tsukemawarashi

Zashikimochi

Tayū were THE courtesans, not only flawlessly beautiful but talented in the arts, conversation, and above all else, performance. The very title originated as a name for the courtesans who were headlining at particular theaters. It was originally a palace lady's rank, but can be glossed as "leading lady" or "diva."

Tayū and koushi were priced out of existence in the Yoshiwara in 1761, but out of respect for the legendary titles, both remained as ranks in the guidebooks for several more decades. (When the ranking above was printed, there had been no tayū or koushi in the Yoshiwara for over 30 years.) Other ranks of oiran became the queens of the Yoshiwara. In Kyoto and Osaka, tayū continued to rule the pleasure quarters. The last tayū house still operates in Kyoto, its handful of women performing dance and song in the styles the courtesans were known for in their heyday.

There are no more women of other ranks. Long before prostitution was banned in 1952, courtesans went out of style, losing their place to the geisha. Their traditions staggered along for a while, ossified and irrelevant, but in the end, their world faded away and was replaced by modern soaplands. The "oiran" who appear in the modern oiran dochū, or procession of courtesans, are actresses.

The very, very short answer: Oiran is a term for courtesans that became popular in Edo/Tokyo. Tayū are the top rank of courtesans in any pleasure quarter.

To go to the list of courtesans' names, click here.

A courtesan went through several changes of name in her lifetime. When she became a kamuro, a child attendant, the brothel owner gave her a simple, childlike name. When she was promoted to shinzō at age 12 to 14 and became an apprentice in a great courtesan's retinue, she took a name containing an element of her "older sister's" name. If she found a good patron and was promoted to an official rank, she took on a full-fledged professional name. Unlike her kamuro and shinzō names, which were written in childlike hiragana, her professional name might be written in sophisticated kanji.

As long as the courtesan was promoted or demoted within the lower ranks of oiran, she probably didn't change her name with each change of status. However, if she was promoted to the top one or two ranks, whatever they were at the time, she entered an entirely different universe. Top-ranking courtesans were artists just like actors and painters. Like actors and painters, they had inherited names—myōseki (名跡)—and these names carried the reputation, the glamour, and the romance of all the women who had borne them before.

Myōseki

According to ukiyo-e scholar Allen Hockley,

Myōseki were the property of the brothel in every sense. The identity and reputation of the establishment were keyed to the history of the names it possessed. The passing of a name from one woman to her successor was the primary means of maintaining continuity and sustaining the prestige of the house. [....] [T]he myōseki were more important than any of the women who held these names. (Hockley, p. 126)

When a woman became a high-ranking courtesan, she stepped into two nested sets of expectations. The first set was the behavior expected of a top courtesan, that embodiment of femininity who was too delicate and refined to eat in a man's presence, but sharp enough to cut him down in a battle of wits and brave enough to stand in the garden of a burning house without panicking. The second set was the behavior expected of the holder of her particular myōseki. This second expectation wasn't as easily defined as "all Segawas are gentle" or "all Takaos are ravishingly beautiful." Rather, it was the interplay of the histories of all the previous holders of the name. The effect must have been like watching an actress play your favorite role: You know the lines, you've seen other actresses play Christine Daaé/Eponine/Juliet, you've heard about brilliant performances from the past, but what will this actress bring to the part?

Preserving the reputation of a myōseki was so important that when the bearer of a myōseki retired, brothel owners didn't hurry to turn it over to a new courtesan. They let it lie unused for a season or more while they looked for a woman talented enough to bear the name. This meant that very rarely did the holder of a myōseki pass it on to a shinzō or kamuro she trained. (Or rather, very rarely did the brothel owners pass a myōseki on to the previous holder's trainee. Unlike artists and actors, courtesans had no say in the transference of their names.)

Although myōseki were the valuable property of particular brothels, the names themselves could be borne by other women. Hanaōgi was a famous myōseki of the Ōgiya, but other houses brought out Hanaōgis, too. Segawa, Komurasaki, Hanamurasaki, all these names appear time after time and year after year in guidebooks from pleasure quarters across Japan. (A study of the guidebooks would tell whether other houses in the same quarter brought out courtesans with the same name when a courtesan bearing the actual myōseki was active. I don't know enough to comment at the moment.) Once a name had cachet, it entered the pool of courtesan names and could be picked up for casual use by any other house. To distinguish between courtesans, people added the name of their house: Hanaōgi of the Ōgiya, Wakamurasaki of the Corner Tamaya, Takao of the Great Miura.

Not all courtesans bore a myōseki; in fact, myōseki were the exception rather than the rule. Every courtesan talented enough to bear a myōseki had several sister courtesans whose names were simply pulled from a pool of names considered elegant enough to be borne by a courtesan.

The Meanings of Courtesans' Names

Yūgiri, one of the most famous courtesans of all time, bore a name from The Tale of Genji that means "Evening Mist." The character Yūgiri was Genji's son, but no one let details stand in the way of a beautiful name.

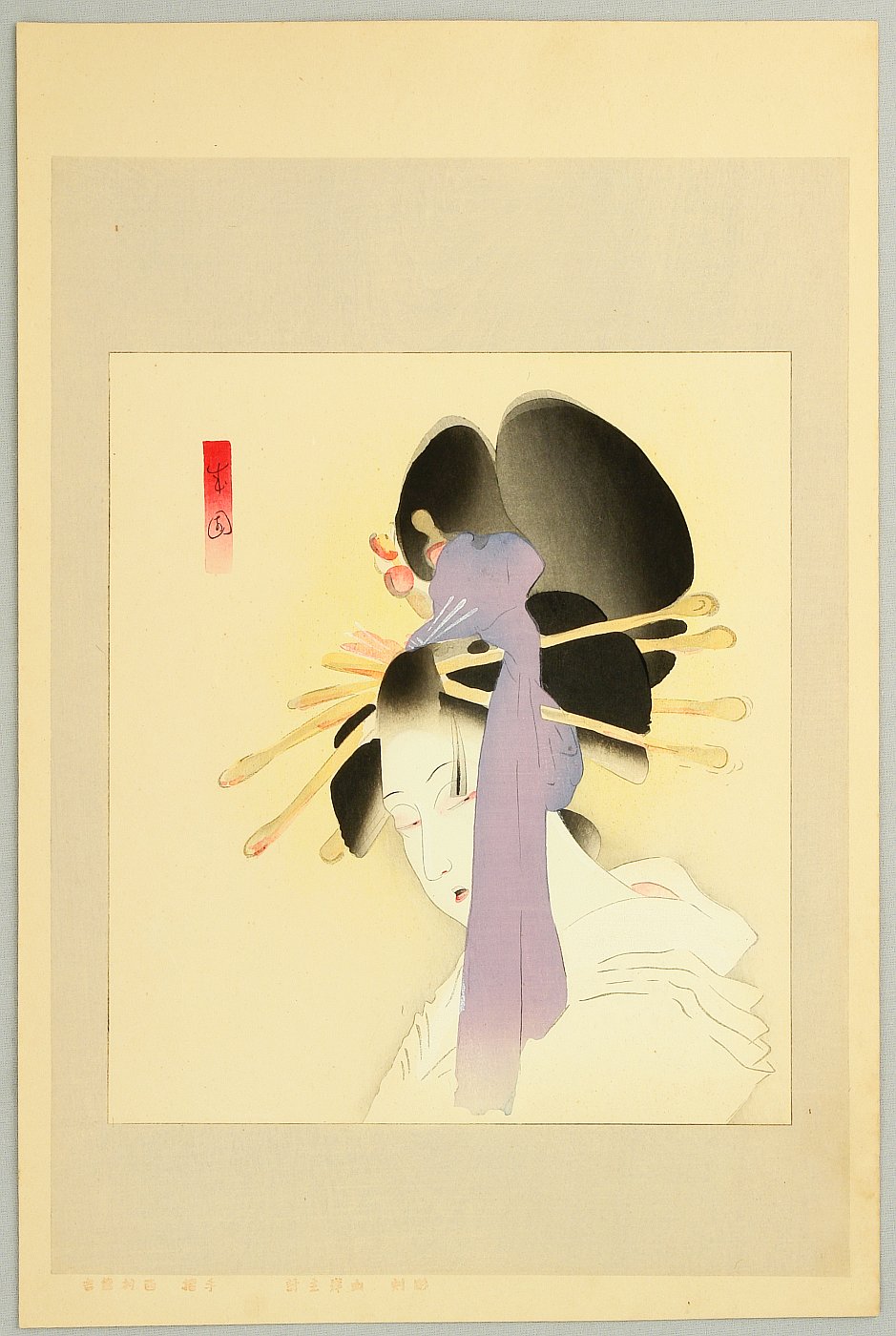

"Yuugiri," by Shima Seien, 1823. [link] © Artelino

Most courtesans' names fell into two groups:

Elegant, Scholarly Images

Genji names. Courtesans combed the great romantic classic The Tale of Genji for names, adopting characters' names, characters' appellations, even the names of chapters: Agemaki, Ukifune, Usugumo, Murasaki (Komurasaki, Koimurasaki, Wakamurasaki, Hanamurasaki). Names from The Tale of Genji were so closely associated with prostitutes that sometimes all prostitutes' professional names were called Genji names (genjina, 源氏名), regardless of whether they came from The Tale of Genji.

Courtesans adopted Genji names in imitation of 16th-century court ladies,[note] who adopted elegant, literary nicknames for use at court. (The first Genji name recorded was Umegae 梅枝, the court name of a lady who died in 1505.[link]) Courtiers eventually stopped using Genji names because they had become so strongly associated with prostitutes.

Literary or historical references. Shizuka was the lover of a tragic hero. Sugawara and Koshikibu were poets. The list of names is filled with references that would have been plain to any educated person of the day.

Poetic images. Aoyagi, "budding willow"; Tamakushi, "jeweled comb"; Kasugano, "a meadow on a spring day." Names based on poetic images sometimes reflected the name of the house: Hanaōgi of the Ōgiya (Flowery Fan of the Fan House), Shiratama of the Tamaya (White Jewel of the Jewel House).

Place Names

Rivers and mountains. Enormous numbers of courtesans' names ended in "river" (-kawa or -gawa, 川) or "mountain" (yama, 山). The name didn't need to refer to a real mountain or river; any beautiful image would do. Courtesans adopted river and mountain names in imitation of 16th-century court ladies, who used them as court names.

Famous landmarks. Some women were named for places known for their beauty or romantic associations, like Takao, which was a mountain famous for its autumn foliage, or Yoshino, a mountain famed for its cherry trees.

General place names. Inlets and seashores, hills and fields. Place names were popular as ordinary girls' names, so it's not surprising that courtesans would take more flowery versions as their professional names.

Daimyō names? Some women took the name of a daimyō who was their patron—at least, that's the story later generations told. It's not clear whether it's true, but some women did have names that were also daimyō family names, which—just to confuse matters—were often place names.

Spellings and Meanings

The spelling and meaning of courtesans' names was fixed. Courtesans did not, as far as I can tell, play the same spelling games that geisha play with their own professional names; each name had a set meaning, and that meaning was expressed with the same kanji. Individual kanji could be replaced with hiragana to make the name easier to read, but this appears to be something people of the period did temporarily, not as a permanent respelling. For example, in modern Japanese, the name Hinazuru written as 雛鶴 means "little tiny stork," while the name Hinazuru written as ひな鶴 is a different name, and it's not possible to say for certain what "ひな" means. In the period when most courtesan names were created, 雛鶴 and ひな鶴 were the same name, and readers were expected to know what ひな meant. [Note: This is based on my own observations of Edo-period spellings, not scholarly references.]

Names of Lower-Ranking Prostitutes

Lower-ranking prostitutes who worked in brothels used the same types of names as their elite sisters. But brothels were only one of the places prostitutes worked. Many inns, bathhouses, and teahouses employed women who were officially servants, but who were bound under the same type of contracts as brothel prostitutes. These women usually took working names that sounded like ordinary female names, but occasionally they might use elegant names like brothel prostitutes, and at least one 19th-century inn gave all its "meal-serving women" geisha names.

Read more about lower-ranking prostitutes' names.

How Did Courtesans' Names Compare to Ordinary Names?

Oh, lord. There was no comparison. Ordinary women were named the equivalent of Mary, Sue, or Ann; courtesans were named Elisiodora or Sophronisba or Sarabella or Persephonitelle. This is a random sampling of Edo-era women's names from Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan:

| Tora Risa Koma Matsu Sen |

Fuku Haru Hisa Tsuya Masa |

Shun Mine Tama Mune Take |

Taki Ine Hide Hatsu Masu |

These plain, short names had plain, short meanings: Pine tree (Matsu), Spring (Haru), Summit (Mine). Most of them referred to domestic virtues or longevity rather than the woman's youth or beauty, and only the tiniest handful derived from poetry or history.

Go to the list of courtesans' names.

References

Japanese Wikipedia: Genji Names. Accessed on Dec. 16, 2014.

Stanley, Amy. Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan. University of California Press: 2012.

Tsunoda Bun'ei (角田文衛). Japanese Female Names: A Historical Perspective | 日本の女性名 歴史的展望. Higashimurayama, Japan : Kyōikusha, 1980-1988.

[note] 16th-century court ladies: Specifically, high-ranking ladies at the shougun's court.

Updated 12/16/2014

Issendai.com

Issendai.com