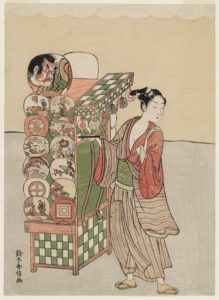

Tokyo has been a shopping mecca for centuries. The Japanese have loved lists and directories for centuries. In 1824, these two loves came together in the Edo Shopping Guide (Edo Kaimono Hitoriannai, 江戸買物独案内), which told the reader all the best things to eat and buy in the city. It listed not only what shops sold and where they were located, but–because shopping was a social experience–the name of the proprietor. Bless ’em. It’s a priceless guide to the names the well-dressed man was wearing in the late Edo period.

The guide is now a searchable database, the Edo Merchant and Craftsperson Database (江戸商人・職人データベースの検索), provided by the National Museum of Japanese History. I downloaded the relevant data, cleaned out (some of) the duplicates, and analyzed it all to hell, and now I’m putting my results online for your delectation and bewilderment.

Notes on the Data

Before the Japanese government ended the practice of name-changing in the late 19th century, a Japanese man changed his name at least once, from his childhood name to an adult name. The name endings most young men used weren’t high-ranking, so if a man went up in the world, he might change his name again. It wasn’t uncommon for a man to bear four or five different names from birth to the grave.

The names in the Edo Shopping Guide are those of grown men, from the youthful/low-ranking -kichi and -saku to the grave, powerful, and fearsome -zaemon. There are a scattering of names that might be boys’ names, particularly the two proprietors named -matsu, but by and large, childhood names are missing from the sample. Boys tended to change their names around 12-21, with a peak in the mid-teens, so if you’re using this list to come up with a name for a young character, you need to look elsewhere. (I’ll have a list of childhood names eventually.)

The names on this list are commoners’ names, not samurai or aristocrat. The Edo Shopping Guide contains a couple dozen samurai/aristocratic names, which I separated out and will publish eventually in a separate list. It also contains dozens of scholarly names, the Chinese-style names that scholars, doctors, and other highly educated men used professionally in place of their personal names. I separated these out as well.

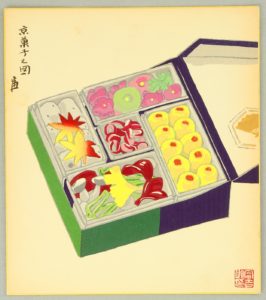

The professions where samurai/aristocratic and scholarly names were concentrated? Medicine and confectionery. Why confectionery? I have no idea. It may have been one of the professions the aristocratic class went into when they lost power, and the income that came with it, at the beginning of the Edo period.

The professions where samurai/aristocratic and scholarly names were concentrated? Medicine and confectionery. Why confectionery? I have no idea. It may have been one of the professions the aristocratic class went into when they lost power, and the income that came with it, at the beginning of the Edo period.